Jennifer Clare Ball, MA, JAMA Network

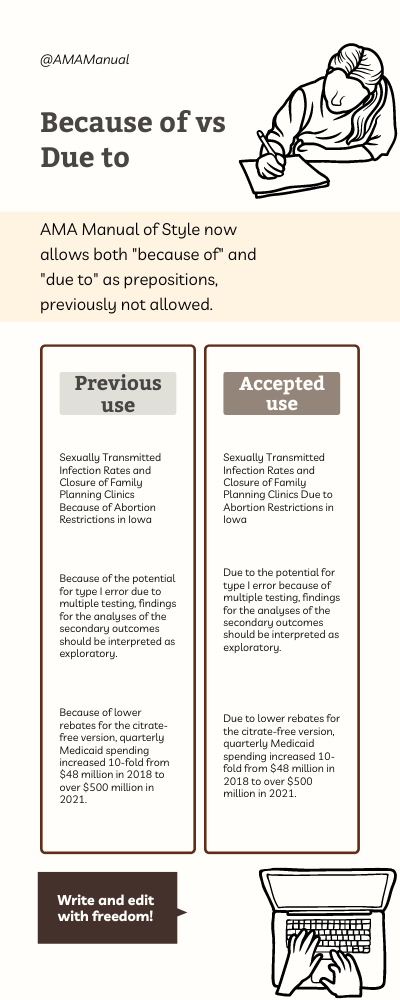

The recent acceptance of due to as a prepositional phrase by the AMA Manual of Style (Chapter 11.1, Correct and Preferred Usage of Common Words and Phrases) is a noteworthy development with substantial implications for professional writers and editors.1

The previous recommendation against its use in this way had sparked debate among grammarians and language enthusiasts, some of whom argued that it should only be used as an adjective phrase modifying a noun.

The relaxation of grammar rules, such as the new guidance on because of vs due to, can positively and negatively affect language depending on the context in which it is used. While it can increase flexibility for writers and make the language more accessible to nonnative speakers, it may also reduce clarity and consistency in some cases. Thus, the creation of official guidance in the AMA Manual of Style is crucial.

The etymology of because of and due to is also worth exploring.2 Because was modeled on the French par cause and has been used with the word of since the late 14th century.

On the other hand, due is from old French deu, past participle of devoir, meaning “to owe.” Due to came about in the early 15th century as “deserved by, merited by,” and its use as a prepositional phrase dates back to 1897.

Current guidance now indicates that because of, caused by, due to, and owing to are acceptable to use as prepositions without restriction.

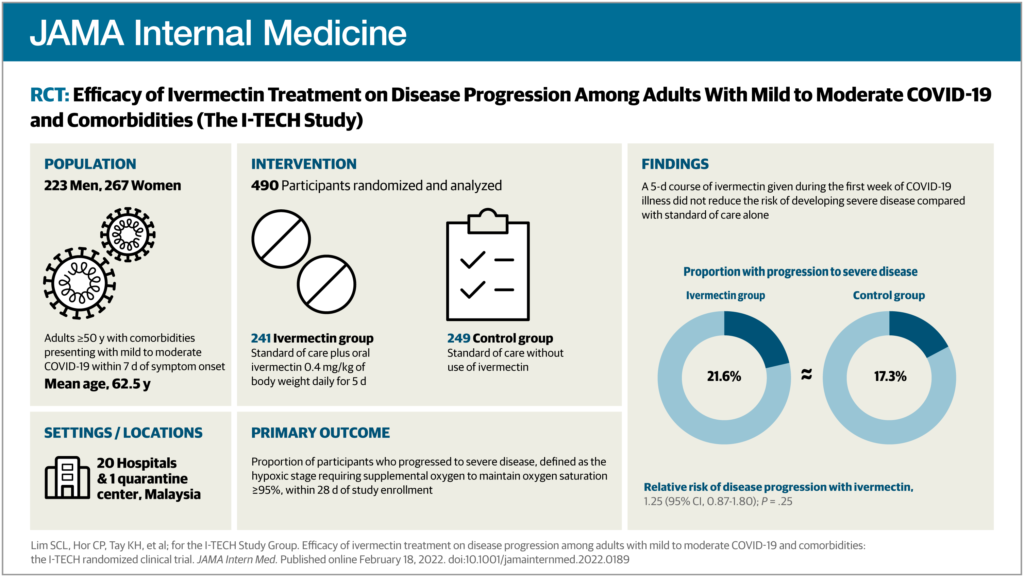

To illustrate the use of due to in medical writing, below are examples from various JAMA Network articles in which the phrase can now be used interchangeably with because of as a prepositional phrase.

The acceptance of due to as a prepositional phrase by the AMA Manual of Style is a notable milestone in the ongoing debate over its use. It provides greater flexibility for writers and editors while ensuring consistency and clarity in medical writing and other communication formats that follow AMA style.

- The AMA Manual of Style now accepts “due to” as a prepositional phrase, which impacts authors and medical editors.

- The debate over “due to” was sparked by its previous disallowance in many instances; some argued for its limited role.

- Relaxed grammar rules can enhance flexibility and accessibility, but may compromise clarity; this highlights the significance of AMA accepting this change.

References

- Frey T, Young RK. Correct and preferred usage. In: Christiansen S, Iverson C, Flanagin A, et al. AMA Manual of Style: A Guide for Authors and Editors. 11th ed. Oxford University Press; 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/jama/9780190246556.003.0011

- Online etymology dictionary. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.etymonline.com/

- Srinivas M, Wong NS, Wallace R, et al. Sexually transmitted infection rates and closure of family planning clinics because of abortion restrictions in iowa. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2239063. Published October 3, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.39063

- Martinez FJ, Han MK, Lopez C, et al. Discriminative accuracy of the CAPTURE tool for identifying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in US primary care settings. JAMA. 2023;329(6):490-501. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.0128

- Wang J, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS, Rome BN. Estimated Medicaid spending on original and citrate-free adalimumab from 2014 through 2021. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(3):275-276. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6299

September 5, 2023.