At the most recent annual conference of the American Medical Writers Association, we received a sneak peek at some of the changes to come with the AMA Manual of Style 11th edition. AMA Manual of Style Committee Members Cheryl Iverson, Stacy Christiansen, and Annette Flanagin gave an overview of some highlights, including changes to the way references are styled, updates taking into account the growing presence of social media, and changes to nomenclature. Other topics included updates to corrections processes, clarification of authorship guidelines, and data sharing rules.

In this post, I thought I’d share some of the changes that I’m most excited about as an editor, many of which promise to make the editing process easier and more intuitive. Several new guidelines for styling references caught my attention. For example, electronic references in the current edition mirror traditional references with the addition of a URL in the middle of the reference and a date accessed at the end. The new edition will put URLs at the end of a reference, similar to how DOIs currently appear. Another welcome change is the omission of publisher locations from references to books and reports, which seems sensible given the multinational nature of publishing and the increasing move toward digital formats.

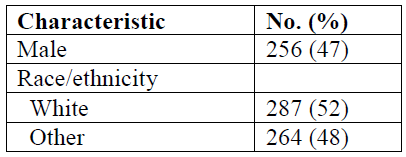

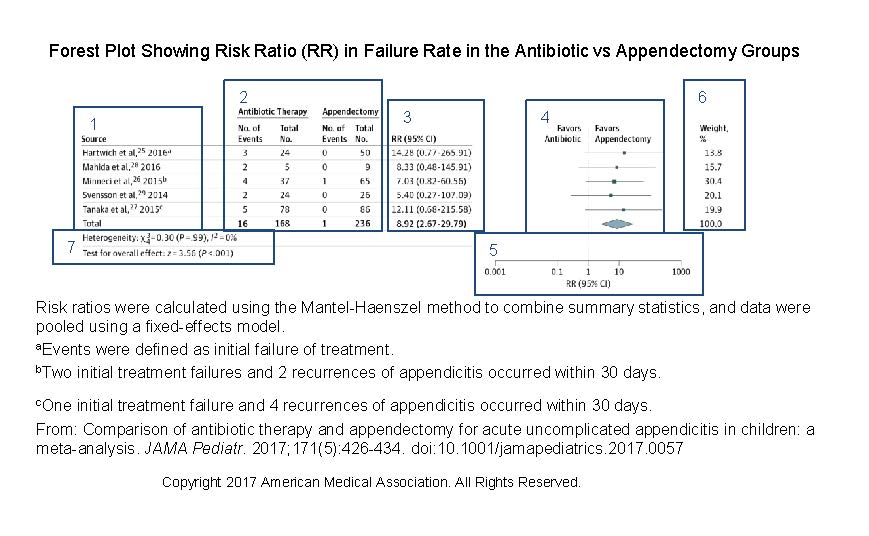

An update to the style of tables and figures was also covered in the presentation. Starting with the 11th edition, column heads in tables and axis labels in graphs will appear in sentence case capitalization rather than title case. Table and figure headings and labels in scientific publishing often contain a great deal of text, making it all the more important to display that text in a way that’s as easy as possible for readers to parse. In addition to saving space, the use of sentence case capitalization throughout figures and tables will make these elements appear more standardized and easier to read.

The new edition also makes some helpful distinctions between AMA style preference and alternatives considered acceptable. For example, it is now acceptable to use of “they” as a singular pronoun. In addition to circumstances in which “they” is a person’s preferred pronoun, this construction can also be helpful in preserving patient confidentiality (eg, avoiding the disclosure of patients’ sex in a small sample size to preserve anonymity).

Many other exciting changes are anticipated with the upcoming 11th edition. Stay tuned for more!—Heather Green