Today is the start of Peer Review Week, an annual global event celebrating the essential role that peer review plays in maintaining scientific quality. This year’s focus is on trust in peer review, and this post addresses the evolving transformation of the peer review in scientific publication.

Peer review continues to develop, albeit slowly, in terms of models and methods, with increasing calls for openness and transparency. There are 3 common forms of peer review:

- Double-blind review: Authors’ and reviewers’ identities are hidden from each other in an attempt to minimize bias.

- Single-blind review: Authors identities are revealed to all, but reviewer identities are not revealed to authors (also known as anonymous review)

- Open review: Author and reviewers are identified are revealed and various levels of the process and outputs may or may not be made public

Types of open review, with increasing levels of openness, include the following:

- Level 1: Reviewer and author identities are revealed to each other during the peer review process

- Level 2: Indication of editor and/or reviewer names on the article

- Level 3: Posting of peer review comments with the article, signed or anonymous

- Level 4: Publication of peer review comments (signed or anonymous) with authors’ and editors’ responses, decision letters, and submitted and revised manuscripts

- Level 5: Publication of the submitted manuscript after a quality check and inviting public discussion from the community

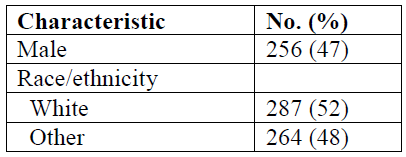

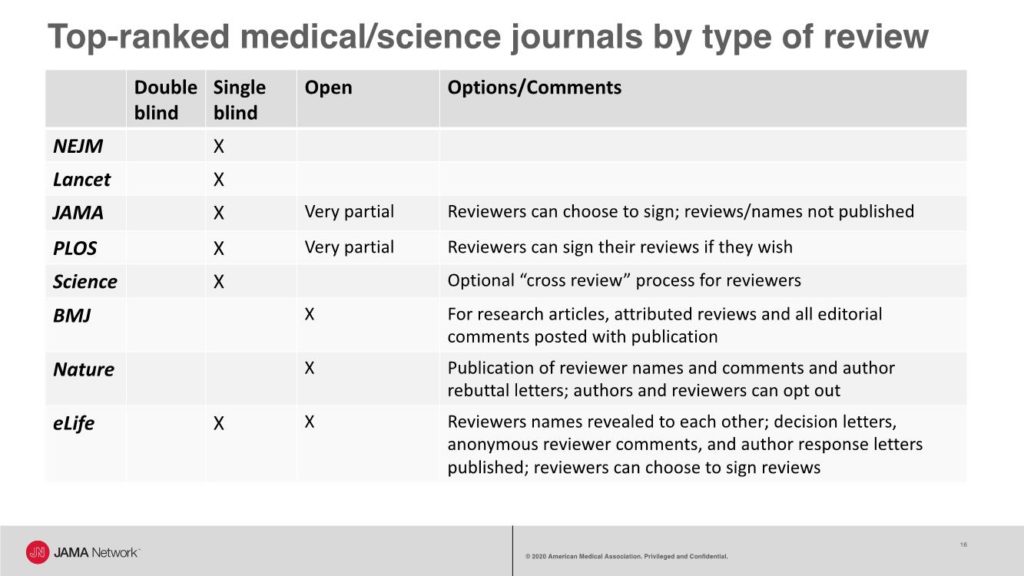

A recent look at the types of peer review used by some top-ranked general medical and science journals shows that most journals use single-blind review, with some allowing reviewers to choose to sign their reviews. For example, JAMA has a single-blind review process and offers reviewers the option to sign their reviews that are shared with authors, and copies of reviews are shared with other reviewers.

JAMA also has an editorial collaborative process, called editorial review before revision, during which senior editors, a manuscript editor, and an editor with expertise in data display collaborate to provide guidance to the authors on all that is needed during revision to reach a favorable final decision.

However, these processes are not public. A short video that explains an inside view of the editorial and peer review process at JAMA is available.

The BMJ has a fully open review process with the following published with all research articles: all versions of the manuscript, the report from the manuscript committee meeting, reviewers’ signed comments, and authors’ responses to all comments from editors and reviewers. Nature publishes reviewer names and comments and author rebuttal letters; however, authors and reviewers can opt out of the open review process. And eLife has a mixed model with reviewers’ names revealed to each other during the review process; decision letters, anonymous reviewer comments, and author response letters published with the article; and an option for reviewers to sign their reviews.

One of the earliest demonstrations of open and collaborative peer review was launched in 2001 by Copernicus Publications, an open-access publisher of scientific journals. These journals use a 2-stage process:

“In the first stage, manuscripts that pass a streamlined access review are immediately posted as preprint in the respective discussion forum. They then undergo an interactive public discussion, during which the referees’ comments (anonymous or attributed), additional community comments by other members of the scientific community (attributed), and the authors’ replies are posted. In the second stage, the peer-review process is completed and, if accepted, the final revised papers are published in the journal.”1

Many studies have compared the quality of single-blind, double-blind, and open review. Early randomized trials2,3 found no differences in the quality of double-blind, single-blind, or open review. But some studies have found differences, such has higher quality for blinded review,4 higher quality for signed reviews,5 and higher quality for open review.6 And some studies7,8 have identified biases that may be better managed with double-blind review (eg, bias toward gender, geography, institutions, and celebrity authors). However, no study has yet compared the quality of published articles that have undergone these different types of peer review.

Drummond Rennie, the founder of the International Congress on Peer Review and Scientific Publication, has been a vocal proponent of open peer review. Writing about freedom and responsibility in publication in 1998, Rennie commented,

“The predominant system of editorial review, where the names of the reviewers are unknown to the authors, is a perfect example of privilege and power (that of the reviewer over the fate of the author’s manuscript) being dislocated from accountability….to the fellow scientist who wrote the manuscript. For that reason alone, we must change our practices. ….The arguments for open peer review are both ethical and practical, and they are overwhelming.”9

There have also been numerous studies demonstrating the feasibility of each type of peer review. However, some studies have found that double-blind review is not always successful and have reported rates of failure to ensure blinding ranging from 10% to 40%. Other studies have found that reviewers who are asked to sign their reviews may be more courteous or positive in their recommendation, may take longer to complete their reviews, and may be more likely to decline invitations to review.

Support for open review, with options, continues to evolve. In a 2016 OpenAire survey of 3062 academic editors, publishers, and authors,10 60% indicated that open peer review (“including making reviewer and author identities open, publishing review reports and enabling greater participation in the peer review process”) should be common in scholarly practice, but they had some concerns. For example, 74% responded that reviewers should be able to choose to participate in open review, and 67% reported being less likely to review if open review was required.

The Nature journals have been experimenting with various models of peer review, and in 2016, Nature Communications announced that about 60% of its authors agreed to have their reviews published.11 In 2019 and 2020, Nature journals began offering “transparent peer review” with options for authors and reviewers to opt out.12

Elsevier conducted a pilot of open review from 2014 to 2017 in 5 journals, with reviews published.13 During this pilot, younger and nonacademic scholars were more willing to review and provided more positive and objective recommendations. There was no change in reviewer willingness to review, their recommendations, or turn-around times. But, only 8% of reviewers agreed to reveal their identities with the published reviews.

Thus, the key to successful transformation to open peer review and maintaining trust in the process may be offering options to authors and reviewers. Whichever model is used, journals should clearly and publicly describe their processes (eg, in Instructions for Authors) and continue to evaluate and test ways to improve the peer review process for authors, reviewers, and editors.–Annette Flanagin, Executive Managing Editor and Vice President, Editorial Operations, for JAMA and the JAMA Network, and Executive Director of the International Congress on Peer Review and Scientific Publication

*Note: Portions of this post have been presented at several meetings.

References:

- Copernicus Publications. Interactive peer review. Accessed August 23, 2020. https://publications.copernicus.org/services/public_peer_review.html

- Justice AC, Cho MK, Winker MA, Berlin JA, Rennie D; PEER Investigators. Does masking author identity improve peer review quality? a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280(3):240–242. doi:10.1001/jama.280.3.240 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/187758

- van Rooyen S, Godlee F, Evans S, Smith R, Black N. Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer review: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280(3):234–237. doi:10.1001/jama.280.3.234 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/187750

- McNutt RA, Evans AT, Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. The effects of blinding on the quality of peer review: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1990;263(10):1371–1376. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03440100079012 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/380957

- Walsh E, Rooney M, Appleby L, Wilkinson G. Open peer review: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176(1):47-51. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.1.47

- Bruce R, Chauvin A, Trinquart L, et al. Impact of interventions to improve the quality of peer review of biomedical journals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 2016;14(85). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0631-5

- Lerback J, Hanson B. Journals invite too few women to referee. Nature. 2017;541(7638):455–457. doi:10.1038/541455a

- McGillivray B, De Ranieri E. Uptake and outcome of manuscripts in Nature journals by review model and author characteristics. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2018; 3(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-018-0049-z

- Rennie D. Freedom and responsibility in medical publication: setting the balance right. JAMA. 1998;280(3):300–302. doi:10.1001/jama.280.3.300

- Ross-Hellauer T, Deppe A, Schmidt B. Survey on open peer review: attitudes and experience amongst editors, authors and reviewers. PLOS One. 2017;12(12): e0189311. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189311

- Transparent peer review one year on. Nat Commun. 2016; 7(13626). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13626

- Peer review policy. Nature Journals. Accessed August 23, 2020. https://www.nature.com/nature-research/editorial-policies/peer-review#transparent-peer-review

- Bravo G, Grimaldo F, López-Iñesta E, et al. The effect of publishing peer review reports on referee behavior in five scholarly journals. Nat Commun. Published online Junary 18, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08250-2